This book review was written by Miriam of the First of May Anarchist Alliance Detroit Collective & originally published online.

In the original review, book titles were underlined; here, titles in the body are bolded instead.

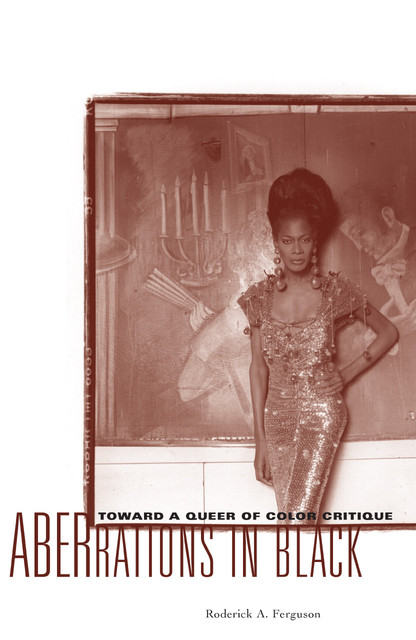

Ferguson, Roderick A. Aberrations in Black. Toward a Queer of Color Critique. (Minneapolis, London. University of Minnesota Press. 2004. Critical American Studies Series.)

I was drawn to this book because of the critical connections it makes between capitalism and left movements that claim to oppose capitalism: liberalism, marxism and revolutionary nationalism. It shows how the acceptance and defense of patriarchy and “normative” behavior serves the needs of capital. It starts from the point of view of people whose self definitions, behaviors and practices are seen as outside respectable, acceptable society: transpeople, people of color, queers, single women, juvenile delinquents, immigrants, prisoners – all of the “others” who have been repeatedly erased, their lives and experiences denied. The cultural site they/we occupy allows us to put forward strategies to demolish capitalism. If our needs are met, if we are a part of the liberatory force, with full respect and dignity, in coalition with others, we have a better chance to avoid cooptation by capitalist forces.

A part of the failure of the marxist and revolutionary nationalist left can be directly tied to their support of patriarchy, their erasure of the needs and experiences of queers and women, their valuing of the nation state as a positive good, able and necessary to achieve stability.

The movement against patriarchy expressed by the predominantly white women’s movement was limited in that it ignored class, gender and racial divisions. It sought to erase the experiences of many women by claiming that all women could achieve equality when the demands specific to their white, middle class experience were met. Victory was tied to the state, as the main demand of that movement was for passage of an equal rights amendment. The need for free, safe abortions, the right to a living wage, demands to meet child care needs, the struggle against rape and violence and for respect etc. were ignored, downplayed, not credited as “winnable” or “reasonable,” often cited as counter-revolutionary.

The gay liberation movement has fought for years for gay people to be treated with respect, not be placed under arrest for their relationship/life/identity choices. The “crowning victory” is the recent passage of the law allowing gay people to marry. This totally ties the movement to the state, to society’s view of what is normal and acceptable. We in M-1 support the right of gay marriage; we support the right of people to express their relationships in whatever manner they wish; we do not confuse this with liberation as we see marriage as the legalized and respectable form the state has designated specifically for intimate relationships. Relationships outside marriage are seen as deviant; partially, the urge toward marriage is the desire to be in a safe, protected relationship with all the citizenship rights granted to straight people.

This book was extremely difficult to read, using vocabulary and language that is sociological and academic – it sent me to the dictionary many times. I struggled to fit meaning into context. For example, “As an epistemological intervention, queer of color analysis denotes an interest in materiality, but refuses ideologies that have helped to constitute marxism, revolutionary nationalism and liberal pluralism.” (3)

In spite of this difficulty, the book is well worth study. I have not found this analysis drawn out anywhere else with the clarity and precision presented by Ferguson.

He does not write about anarchism, nor does he present a direction toward a revolutionary overthrow of society. However, as anarchists with a definite purpose to overthrow capitalism and replace it with a free society, we will do well to take into account the connections he draws. We must not erase all of us drawn outside society’s definitions of normal – all of us, people of color, women who do not tie their identity to a man, queers, trans people, immigrants, disabled, prisoners, all the varieties of gender and sexuality choice that are available to us as creative people true to our own feelings, identities and pursuits of happiness and liberation.

We start from the point of view of the trans person of color, representing all the people and categories that are denied status, citizenship rights and protections.

Marxism, revolutionary nationalism and liberalism all assume that the heterosexual patriarchal family is the natural and normal relationship within which women find their true satisfaction and men find peace and contentment. This is the place where all the fears and hurts of living are soothed, where comfort can be found. This is where morality and values are taught. This is also the source of economic support, where the man’s wage is intended to maintain the entire family. The unpaid labor of the housewife, cleaning and maintaining the home, raising the children, providing sex and comfort is her contribution to this effort. Inside this fiction, woman’s place is in the home, man’s place is in public. Any woman stepping out into public becomes fair game, an unmoral woman, a prostitute.

Identities, relationships and practices that diverge from this are labeled deviant and pathological. Their presence is erased and/or regulated.

The intersections of class, race, sexuality and gender provide a place to open up discussion of how these different ideologies are all used to facilitate the needs of capital. By opening up what has been kept closed, we can point our critique at one of the root causes of our oppression. We can find ways to critique and counter this oppression, thus strengthening our own movement of opposition.

Marx uncritically accepted the bourgeois attitudes of the 19th century British middle class. He saw the growth of industrial capitalism as a disruption of man’s natural division of labor, that of the heterosexual patriarchal family. Marx used the symbol of the prostitute to represent this disruption.

Prostitution is the symbol of man’s feminization, the removal of his manly essence. Wage labor didn’t allow a man to be himself; the wage laborer prostituted himself, sold himself, to the capitalist.

Capital needs a ready supply of labor. In its expansion, it encouraged movement from rural areas to the cities. Capital doesn’t really care about social costs and leaves it to the state to handle the social anxieties and disruptions that are caused by migrations. When the social regulations of homogeneous rural areas are disrupted, the bourgeoisie look to the state to maintain social order. Some of this takes place as laws, some as culture, what is generally acceptable behavior.

In 19th century Britain, white working class girls were seen by the middle class as pathologically sexual, rootless and uncontrolled. (9) Their desires for commodity items, clothes and hair ribbons were seen as awakening their sexual appetites, driving them into prostitution. At this same time, the Hottentot Venus (Sarah Bartmann) was put on display in venues around London, tying the middle class fear of sexuality to Black women’s bodies.

In 19th century United States, Chinese laborers were imported to lay track for the railroads. Immigration of Asian women was prohibited by exclusion laws, resulting in mostly male communities. They were marked as deviant, not normal, their deviance tied to their race as well as their class and sexual situation.

Industrial expansion in the southwest part of the United States in the early 20th century created the demand for low wage labor. Over 1 million Mexicans immigrated to the United States. “Americanization” programs were designed and used to train Mexican women to be acceptable as domestic workers within white households.

The demands of northern capital, as well as the horrors of post-slavery, defeated-Reconstruction life in the south, led to the mass migration of African Americans from the south to the northern cities. Upon arrival, they were restricted to living in ghetto sections of the city and limited in what jobs were available. Vice sections were moved from suburbs and concentrated in the African American area of the cities. This identified vice with African Americans and vice versa.

“The state’s regulation of nonwhite gender and sexual practices through Americanization programs, vice commissions, residential segregation and immigration exclusion attempted to press nonwhites into gender and sexual conformity, despite the gender and racial diversity of those racialized groups.” (14)

Canonical sociology provided the language to discuss the changes occurring in the United States. It defined African American culture as a culture of difference and deviance. “The. . . writings about race. . . served. . . to organize and alter the aspects of social life they reported on or analyzed.” (19)

They no longer labeled African Americans as biologically inferior; they now were labeled as culturally inadequate. Their culture was blamed for the poverty and all the social dysfunction experienced by the community. Black households, especially female headed households, were seen as incapable of socializing their members into socially acceptable behavior. (19)

The higher economic and social costs of living in cities were displaced onto the family. Well paid wage labor was reserved for white men; African Americans were limited to temporary, low wage, service types of employment, or the dirtiest and hardest manual labor. Child raising remains the responsibility of African American women, who must also work for wages.

The state demands that the family absorb the costs that capital will not pay for – economic like providing food, shelter, clothes and social, like child raising, emotional connection, love and sexuality.

“By naturalizing heterosexuality as the only possible, sensible and desirable organizing principle by which society and social relations can function, canonical sociology aligned itself with the regulatory imperatives of the state against African Americans.” (20)

The concentration of the vice and entertainment district in the African American community also allowed for the emergence of a space that was outside the regulated and normative spaces of acceptable society. Here was a place where Black and white could mingle, homosexual and heterosexual, trans people could all be together. This did not, of course, leave systemic and individual racist and sexist attitudes and practices behind, but it did provide a place of connection, a space where one could be themselves, in company with others like them. In this place, a critical view could be developed, connections could be made, an opening wedge formed against the narrow exclusions of society.

African American literature first developed as a way to assert humanity, the right of African Americans to be treated as equal men and women. It also opens up the many and varied possibilities of cultural forms outside the acceptable. Literature can be used to regulate behavior, to define what is/is not pathological, to set boundaries. It can also rupture those boundaries, present and explore new possibilities and ways of being.

The chapters in this book are organized to present classical works of African American literature, situating each of them in their own context and period. Ferguson draws out the dynamic connections between each work, how it reflects the needs of liberal capitalism in each specific period, and how it is used to bolster (or critique) the system. Chapter one discusses Richard Wright’s Native Son in the context of the influence of the Chicago School of Sociology and the New Deal. Chapter two discusses Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and the role of education and college in acculturating African Americans into a white middle class citizenship ideal. Chapter three sets James Baldwin’s Go Tell It On the Mountain against Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma. It discusses rationality and the drive of the United States to represent itself as the ideal expression of rationality and world morality. Chapter four uses Toni Morrison’s Sula to open the discussion of Black women’s feminism and lesbian feminist organizing and theorizing toward coalition of openly expressed differences. He discusses the Black Panther Party and how revolutionary nationalism also naturalizes hetero patriarchy, forming an alliance with liberal capitalism. He finishes the book with a discussion of post American studies and how a critique of the normative in all its aspects is crucial to an understanding of the globalization phase of capitalist expansion.

Capitalism has continually found ways to co-opt movements ostensibly against it; it has set “respectability standards” that allow a few working class and/or people of color and/or homosexuals to pass through and win their citizenship rights by helping to regulate the rest.

Chapter one. The Chicago School of Sociology, Richard Wright, Native Son, New Deal liberalism and Wright’s understanding of Marxism all share the same assumptions about what are normal expressions of gender and sexuality. For New Dealers, social policy was tied to “responsible intimacy.” (27)

Benefits were allocated on the basis of women’s status as wives and mothers. Women’s economic security was tied to men’s wages, ADC, widow’s benefits. White men’s economic security was tied to fair wages, guaranteed by unions, and social insurance.

Female headed households in the African American community were regarded as immoral and were excluded from New Deal policy gains. The Feds deferred to the States to determine need and fitness for benefits. State’s laws against unwed motherhood justified the denial of benefits and protection. The Social Security Act excluded domestic and service workers, along with casual and agricultural workers. These types of employment were tracked according to race and so the exclusions became racial exclusions.

They were also subject to relentless observation, surveillance and regulation. There are many stories of welfare workers looking for signs of a man’s presence in a female headed home. Ford used the same surveillance tactic to control his workforce, requiring church attendance and a Bible in each home. Single mothers in public housing today are also subject to this same observation, surveillance and regulation.

White women were discouraged from wage earning work in order to guarantee the stability of the household. Her unpaid work was necessary to the stability of the family unit. In our current period, white women are allowed to work outside the home, being normalized and accepted as citizens because they are white.

African American women were seen as appropriate wage earners, keeping them in the public and accessible to white men. This also prevented them from sustaining hetero patriarchal households. They were sexualized so that their Black bodies represented sexual availability, immorality and deviance, unrespectability. The desire of African American women to express their felt sexuality has been in constant conflict with the desire of the community to present itself as respectable.

Because “non white communities were racialized as non hetero normative, hetero patriarchal regulation enforced the racialized boundaries of neighborhood and community.” (39) The limiting of vice to African American neighborhoods worked together with residential segregation. This established a formal relationship between racial exclusion and sexual regulation.

Richard Wright saw Marxism as the revolutionary force that could unite all the different ethnic groups he saw pouring into Chicago, working together in the steel mills and slaughter yards. In his text, Native Son, he sees what he considers the perversions of his own community as a part of the feminizing, castrating effects of capital on the worker. “Economic subordination intersected with racial subordination through the denial of patriarchal status to Black men.” (44) Wright used sociology and scientific findings, highly valued throughout the progressive and liberal community, to describe vice districts as social disorganization, the juvenile delinquent and homosexual as perversions. Wright and marxists and revolutionary nationalists all call for a specifically masculine revolutionary agency to oppose the feminization caused by capital.

They work to erase sexual and gender diversity, thereby serving the needs of the liberal state in its attempts to universalize lived experience as class and race, ignoring the subjective experience of sexuality and gender. In their view, the virile and masculine folk hero has to emerge to replace the deviant and dysfunctional female head of household.

Native Son develops the theme of juvenile delinquency, located in lower class African American families headed by women. Bigger (the juvenile delinquent) is feminized, humiliated as a worker, and infantilized as his mother’s son. He is unable to get beyond or transcend social disorganization and is linked with other representations of dysfunction – unwed mothers, transpeople, criminals, homosexuals, delinquents. He is not a “stable representative of African American revolutionary nationalism.” (53)

Chapter two discusses Ralph Ellison’s classic novel, Invisible Man, using a chapter that was removed from the final version before publication and found in the Ralph Ellison Papers in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. In this unpublished chapter, the main character, Woodbridge is an African American homosexual, a teacher warning his student of the dangers of stepping outside the normative bounds of the college. Self regulation is promoted as the key to progress, maturity and the rights of citizenship. Woodbridge represents the nonconformity that educational institutions, along with Americanization programs and citizen-preparation classes are designed to erase. These narratives, at the center of Invisible Man, construct African Americans as people who might fit into the normative bounds of citizenship (55), if they are regulated, either by themselves or by an outside agency.

“A fundamental feature of canonical formation is their attempt to unify aesthetic and intellectual culture by reconciling material differences. This fails because material differences themselves contradict pronouncements of unity.” (55) This false unity forms the basis of national identification – we are all citizens.

College promises to rid its students of any differences that interfere with their transformation into acceptable citizens. In particular, the HBCUs (historically Black colleges and universities) were driven by the unspoken anxieties about their own non-normativity. (60) Heterosexual regulation is part of the racial regulation of an African American college student. (62)

Institutions were also used to discipline immigrants, non-Western populations to make them conform to national ideals, set by the liberal state.

Promises of the benefits of citizenship are in fact techniques of discipline. (65) Self regulation, which is in fact self negation, is how one is told to achieve progress. The right to citizenship is achieved through hetero normative regulation.

The concept of diversity arises out of liberal ideology. Rather than “resolving the inequality that characterizes liberal capitalism,” (71) it works to conceal capitalism’s economic and social contradictions. The state and capital use class, racial, sexual and gender difference to exclude people from the rights of citizenship. The “rhetoric of diversity” (71) conceals that exclusion. It pretends that capitalism can solve its own problems.

Ferguson cites Foucault in his discussion of the confessional as the way to truth of sexual practices.

The sociologists turned these interior features of consciousness into exterior features, using neighborhoods, intimate arrangements, gender formations to “articulate the sexual truth of racialized subjectivity.” (74)

The moral and subjective life of African Americans was subjected to intense surveillance, speculation and discussion. They were presented as unpredictable figures in need of moral regulation by bourgeois culture.

African American middle class persons had to publicly demonstrate compliance with hetero patriarchal cultural standards in order to prove their distance from lower class African Americans, as a way of claiming access to citizenship.

African Americans seeking normalization were told by, for example, the Urban League to exhibit “restrained and disciplined behavior” and make themselves available for surveillance in the name of recognition and normativity. (75)

“Statistics emerged as apparatus for tallying African American’s cultural dysfunction for the good of liberal capitalist stability. Statistics were used as a “technology of race.” (76) Statistics are gained by surveillance, itself defined as scientifically acceptable and as a socially necessary practice. Housing and neighborhood conditions, illiteracy and poverty became omens of pathology. For African Americans the body itself became identified as the site of these pathologies.

“By making the social a sign that had to be disciplined for its racial gender and sexual truths, it became possible for racialized surveillance to operate as a scientific discourse.” (78)

The resolution of any ideosyncracies was determined to be through state intervention. This is tied to an “hysterization” of Black women’s reproductivity. Marriage was the factor that determined whether reproduction was healthy or a sign of social disintegration.

“Sociology made the production of racial knowledge about African Americans into a political economy of sexual knowledge in which Blacks could be used to justify the extension and support of normative presumptions about American citizenship. Sociology helped to corroborate the expansion of state power by legitimating surveillance as a vital scientific and social endeavor. During and after World War II canonical sociology would proceed to crown the United States nation state as the heir to Western rationality, sketching it against a discursively manufactured African American Other.” (81)

Chapter three sets James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain against Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma.

In this post world war II period, cracks were appearing in the monolith presented by the United States. Women were found more often in the public sphere, not willing to give up the jobs and freedom they represented. African Americans were stepping up their struggles for civil rights. National liberation struggles around the world were gaining support. Social order depends on the suppression of the intersections of race class gender and sexuality. Baldwin exposes these differences; Myrdal conceals them in his efforts to portray the United States as the epitome of Western rationality.

Ferguson discusses Max Weber and his theories of rationality. Rationality operates by regulating sexual expression through hetero patriarchal intimate relations. He discusses the relation of sex to religion, once very intimate, later divided through the intervention of the “cultic priesthood” (84) regulating sex through marriage.

Slave emancipation in the United States enacted a demand for sexual regulation. It was a foremost concern of the Freedman’s Bureau. “Those newly freed African Americans who rejected marriage and monogamy were imprisoned and/or denied pension payments.” (86)

“Future material contradictions could be displaced onto African American intimate relations as the state regulated heterosexual marriage, making the husband legally responsible for the function and care of the household. By doing so, the state could shift the care of freed slaves from the state and former slavemasters.” (86)

Chapter four discusses the important emergence of Black women’s feminism as a different way of approaching the particular experiences that are left out of revolutionary nationalism, marxism and (white) feminism. It shows how these movements, in their erasures, serve the liberal capitalist state.

Women of color and Black lesbian feminist theorists noted the importance of expressing difference, and bringing different people together in coalition, without erasing those differences.

“We may also situate women of color feminism within the limitations of national liberation movements and at the cusp of global capital’s commodification of third world and immigrant labor. . . .The discourse of [Moynihan’s] Black matriarchy justified and promoted the regulatory practices of the state and the exploitative practices of global capital as the United States nation state began to absorb women of color labor from the United States and the third world as part of capital’s new regimes of exploitation.” (111)

Women of color feminism emerged “after the period that Immanuel Wallerstein dubs the “second apotheosis of liberalism,” from 1945-1970, when liberal ideology seemed to have flourished globally.” (112)

Western nations were turning away from past blatant oppressions, national liberation movements were coming to power. The United States claimed a commitment to civil rights, passing a range of civil rights legislation. Revolutionary nationalist organizations, like the Black Panther Party, rose to challenge the claims of the United States. However, they maintained an “investment in heteropatriarchy.” (113)

Ferguson develops the idea that the national liberationist drive to “preserve the positive values” in developing the new nation aligns it with a view that is against the non normative. It accepts liberal capital’s definitions of normal, in much the same way Marx uncritically accepted the bourgeois values of his time.

Exploitation and colonialism is seen to disrupt the natural hetero patriarchal status of the man; to feminize, humiliate and demean him. He can only achieve liberation with the reestablishment of the natural order. Ferguson quotes Huey Newton: “If he can only recapture his mind, recapture his balls, then he will lose all fear and will be free to determine his destiny.” (115)

In fact the revolutionary nationalist movement boxed women into acceptable roles and erased the homosexual. Because of this denial, women and gay people had to speak for themselves, began to write their own truths and developed their own movements.

In the United States the emerging (white) women’s movement “engaged in racial and class exclusions. . normalizing white citizenship; the civil rights movement complied with liberal exclusions through its sexist ideologies and practices, thereby normalizing hetero patriarchal citizenship.” (115)

Despite antagonism to liberalism, [revolutionary nationalism] “facilitated liberalism’s triumph.” (115)

It is the women of color movement that has called out these problems in the movements against United States domination. They have addressed the convergence of Black power, civil rights and United States nationalism by making the distinctions of identity that these other movements have tried to erase. They have challenged state power and the right of the state to exercise its power. They have claimed the right to identity without making that identity a condition for coalition or struggle. They have sought to express the truth of their own lived experience and use these truths to expose the hypocritical nature of liberal capitalism and the inadequacy of nationalist and liberal movements to combat capitalism.

The Moynihan Report, “framing itself as a document interested in advancing the gains of civil rights,” (119) presented the discourse of the Black matriarchy. It claimed that the fundamental roadblock to the attainment of full civil rights for the African American was the matriarchal family structure found in the African American community. Civil rights legislation, job programs and the like all provided opportunity, but did not ensure results. “Equality of outcome. . .depended on the gender and sexual compliance of African American culture.” (121)

This “discourse facilitated a conservative blockade of social welfare policy.” “Displacing the contradictions of capital onto African American female headed households established the moral grammar and the political practices of the very neoconservative formations that would roll back the gains of civil rights in the 1980s and 1990s and undermine the well being of Black poor and working class families.” (124)

Neoconservatives explicitly based their objections to public spending on the discourse of Black matriarchy, arguing that “welfare queens” were “getting fat off liberal social policies.” (125)

It is during this period that Black women’s writing and Black lesbian feminist writing in particular entered the cultural battles. By arguing that “if identity is posed, it must be constantly contravened,” (127) it exposed the contradictions that nationalism strives to conceal. “Rather than naming an identity, “lesbian” actually identifies a set of social relations that point to the instability of heteropatriarchy and to a possible critical emergence within that instability.” (127)

Black lesbian feminist organizations and activists came from a diverse range of social movements – women, anti war, civil rights, Black power. The Combahee River Collective, formed in Boston in 1974 had a notion of Black women as queer, anti racist, feminist and socialist. The Salsa Soul Sisters Third World Womyn Inc., also formed in 1974 were comprised of African American, African, Caribbean, Asian American and Latina women. “The class, national, ethnic, political, sexual and racial diversity that made up Black lesbian feminist organizations compelled articulations of Black feminism and Black womanhood that allowed for such multiplicity.” (129) This heterogeneous composition inspired a politics of difference that could critique nationalist underpinnings of identity. It challenged racial regulation and gender and sexual normativity. They dealt with the questions of how an oppressed subject can also be an oppressing subject, often within the difficult context of coalition work.

Toni Morrison’s Sula was published within the period that occasioned the upward and downward expansion of Black social structures. The economic changes of the 1970s launched some African Americans into middle class lifestyles and locked others into poverty. (130) This was part of a global trend as the economies of highly industrialized countries shifted toward service economies. The redeployment of manufacturing and office jobs to less developed areas created a significant increase in low wage jobs, particularly female-typed jobs in highly developed countries.

The discourse of Black matriarchy helped constitute the upward and downward expansion of African American social structure as the polarization of hetero normative and non hetero normative African American social formations. (131) The single Black mother and the Black lesbian were the female-outsiders as against normative Black middle class women who claim legitimacy within African American communities. This middle class formation negotiated the upward and downward expansion by regulating and differentiating the other.

In his conclusion, Ferguson states that “our current moment requires an analysis of social formations that can illuminate how the intersections of gender, class and sexuality variegate racial and national formations within the current phase of capital.” (137) The negation of normativity and nationalism is the condition for the development of critical knowledge.

National liberation’s investment in hetero patriarchal ideals produced present day conditions in which advanced capitalism and post colonial formations intersect through hetero normative regulation through the creation of a regulatory middle class. Post colonial middle classes have based managerial legitimacy on their ability to deliver indigenous economies and labor over to the needs of multinational corporations. That legitimacy cannot be separated from the needs of elites to construct themselves as ideally hetero sexual and patriarchal, and therefore, fit for governance.

In the United States, the transition from an industrial economy to a post industrial economy has led to the decline in manufacturing jobs, an increase in service jobs, along with an increase in private sector and government jobs, which promotes the development of elite formations among African Americans.

This “new” African American middle class bases its legitimacy on its ideological and often administrative role as the overseer of queer, poor, HIV-positive, drug addicted persons in African American communities, becoming the normative antithesis to deviant African American subjects. (145)

Immigration policy is also being shaped within the context of struggles over queerness, race and normativity.

I am hoping that the above discussion will inform our politics as we struggle to create a revolutionary anarchism that can speak to and for all of the “others” labeled as deviant, criminals, thugs, outside the acceptable boundaries of respectable behavior. We in M-1 are a “coalition” of women, men, other-gender-identified, gay, straight, other-sexually identified, all races, religions, ethnic backgrounds, poor and middle class, working class people. We are united around a common politics and a shared commitment to the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism. We are against states and governments and all forms of regulation that limit our development as free creative and expressive persons determining our own lives and futures.